Lentils and beans instead of forage maize

Our traditional diet is putting pressure on the climate, water and soil. ZHAW researchers are investigating how more plant-based foods can be grown on Swiss fields.

Today, around 60 percent of Swiss arable land is used to grow animal feed. To feed all the cows, cattle, pigs and chicken, it is also necessary to import soya and grain from abroad. Our preference for meat, dairy products and eggs is causing major environmental impacts, including greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, a decline in biodiversity and in soil fertility. To counter these challenges, we urgently need to change both our diet and agricultural practices.

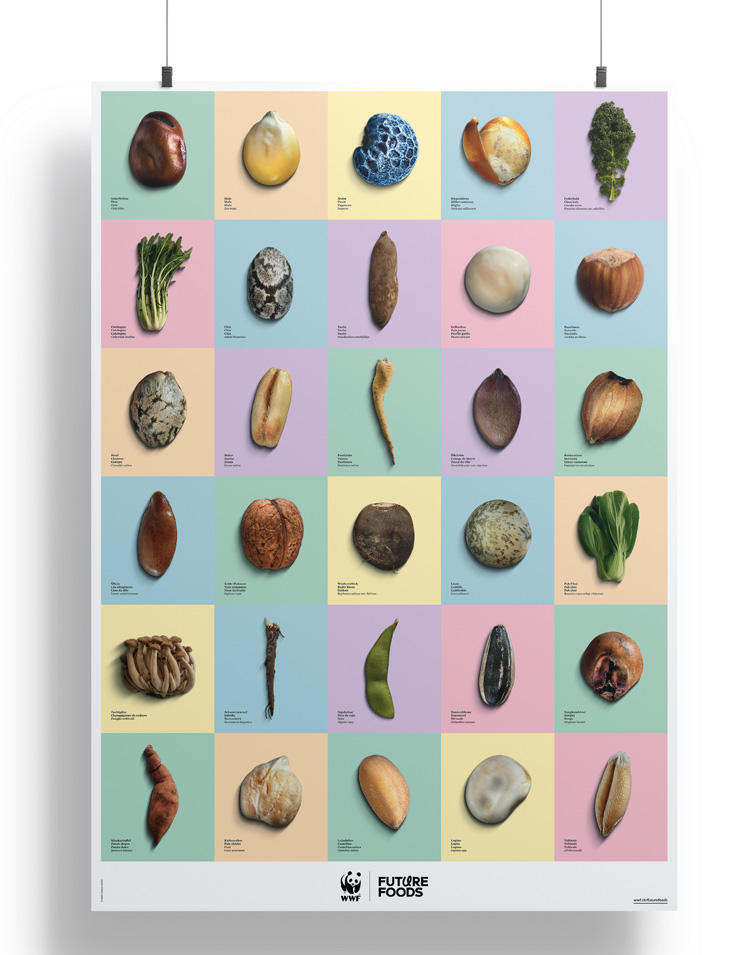

At the Institute of Natural Resource Sciences (IUNR), various aspects of this transformation are being explored. For example, the Geography of Food Research Group has defined 30 so-called future foods on behalf of WWF Switzerland. These include vegetables like kale, catalogna (an Italian variety of chicory) and black salsify (a root vegetable), as well as carbohydrate sources such as sweet potatoes and sorghum, and legumes like soya, lupins and broad beans. At the outset of the project, more than 100 varieties were considered as potential future foods. When narrowing them down, experts analysed whether they are suitable for local weather conditions, how cultivation affects biodiversity and soils, which nutrients they contain and what their market potential is. The best-performing varieties were included in a brochure and a website with recipe ideas and detailed information on nutrients. With this stock of information, WWF ran a campaign last year together with major retailers. “The 30 recommended foods offer a wide range of uses and can make an important contribution to a healthy and more environmentally friendly diet,” says project leader and IUNR lecturer Roman Grüter.

Legumes instead of meat

One goal of the research group is to promote what is often called the protein shift: In order to meet our daily protein needs, legumes, nuts and seeds should increasingly replace animal products on our plates. At present, however, these plant-based protein sources are primarily imported from abroad, while Swiss agriculture remains heavily focussed on livestock and dairy farming. This approach is justified in mountainous areas where arable farming is challenging, says Grüter. “But the narrative of Switzerland as a grassland country is only partly true.” Even in the lowlands, a large proportion of the soil is used to grow animal feed such as maize, barley and artificial meadows. The latter refer to sown meadows that are home to various grasses and clover. For a crop rotation that maintains soil fertility in the long term, artificial meadows are valuable, adds Grüter. “However, depending on the location, a reduction in the share of artificial meadows could result in additional land for crops that serve direct human consumption.”

Involving all stakeholders

As part of another project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the researchers at the ZHAW campus in Wädenswil are investigating the potential of legumes and oil plants in Switzerland. In doing so, they are looking at a wide range of factors – from cultivation, environmental impacts and processing options to acceptance among farmers, marketing organisations and customers. Policy-driven incentives are another area of focus. “At present, the cultivation of protein crops for direct human consumption is not strongly subsidised when compared to animal-based foods,” says Roman Grüter with a sense of regret. For farmers, switching to these crops is therefore hardly worthwhile. On top of that, crops such as lentils, broad beans, soya and protein peas are more dependent on weather conditions than meat and dairy production. “In a rainy summer, the worst-case scenario could be a total crop failure.”

“Locally sourced food strengthens our relationship with the products and increases our willingness to pay fair prices.”

That is why stepping up research to breed varieties that can thrive under local climatic conditions is crucial, the environmental scientist emphasises. It is therefore vital to involve all the relevant players in the food system in our studies. In addition to the farmers, this also includes processing and transport companies, retailers, restaurateurs, consumers, politicians, authorities as well as environmental protection and health organisations. “A participatory approach helps us to gain practical insights and knowledge and allows us to develop solutions that work in the real world,” explains Grüter. In workshops, participants discuss topics such as food trends, climate change and political conditions from their different perspectives.

Products from nearby farms

Local roots also need to be strengthened. In the three pilot regions of Knonauer Amt (near Zurich), Baselland and Yverdon-les-Bains, the researchers are currently promoting regional food system networks. The aim is to create sales markets for organic products with short supply chains, for example through weekly markets, vegetable box subscriptions or smaller shops with local produce. In larger cities, such offerings have existed for some time, says research associate Sonja Trachsel, but in rural regions, by contrast, there is still potential. “Locally sourced food strengthens our relationship with the products,” explains Trachsel. According to her, this increases the willingness to pay fair prices, which in turn secure better incomes for farmers. In Wädenswil, a regional transformation project is already up and running as part of an initiative called Ernährungszukunft Wädenswil (“Food of the Future Wädenswil”). Its goal is to promote a sustainable agriculture and food industry, for example by encouraging institutions to use more local products and educating retailers and restaurants about the shelf life of food in order to avoid food waste. Financial incentives for farms that produce in a climate-friendly manner are also being considered.

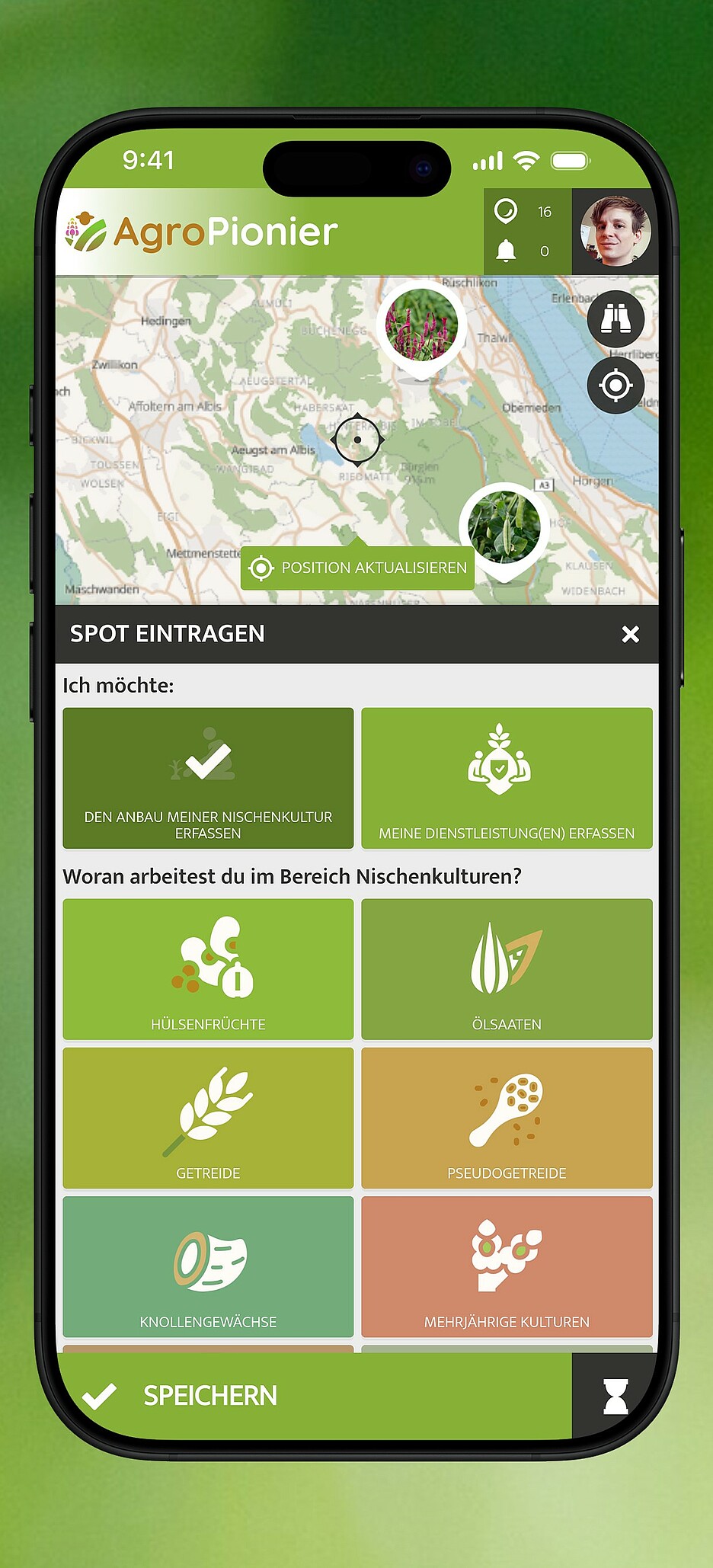

App for sharing knowledge on niche crops

Brigitte sowed winter lentils this year. Thanks to dry weather, plenty of wind and patience, it has gone surprisingly well, writes the farmer on the agricultural app AgroPionier. Roman enquires about the yield, and Brigitte replies that after drying, it was about 1.4 tonnes. The app and the associated website have been developed by the Geography of Food Research Group together with the University of Zurich and Strickhof, a centre of expertise for sustainable food systems. Third-party funding came from the fund of the Digitalization Initiative of the Zurich Higher Education Institutions (DIZH).

Since February 2025, the digital applications have been available to farmers who want to exchange their experiences with niche crops. These include linseed, farro, salsify, broad beans, lupins and other legumes. Some of these are traditional crops that are now rarely grown in Switzerland. Today, more than 80 percent of Switzerland’s arable land is used for just six different crops: wheat, maize, barley, rapeseed, sugar beet and potatoes.

To withstand increasing weather extremes caused by climate change and to produce more plant-based food, diversification is essential. However, innovative farmers are often left to their own devices, observes project leader Roman Grüter. “We want to work with them to generate new knowledge about the cultivation of niche crops.” AgroPionier uses what is known as the farmer science approach, which involves farmers in data collection and analysis. Results from research as well as services such as drying and processing options are also recorded in the app.

0 Comments

Be the First to Comment!