Helping ideas for a circular economy to take off

The ZHAW conducts research into circular products and business models and supports companies in implementing their ideas. The Institute of Product Development and Production Technologies places a particular focus on this area. An interview with Institute Director Adrian Burri.

Mr Burri, a circular economy is viewed as offering a magic formula for sustainable business. What does it mean exactly?

Adrian Burri: The circular economy is an approach aimed at solving and bringing under control the problematic consequences stemming from the current linear economy, including the climate crisis, a scarcity of resources and environmental pollution. Instead of continuing to exploit nature and the environment while emitting huge volumes of CO2 and generating mountains of waste, materials such as textiles, plastics and metals should be able to be used time and again.

This doesn't work with all materials.

Burri: This is the big challenge faced during product development. In the case of most materials, downcycling is the only option. For example, a piece of clothing can at best be turned into a rug, but not into a new garment. At our institute, we conduct research into solutions for designing products that only use circular materials and develop production processes for new materials.

Which materials are particularly suitable?

Burri: Generally speaking, metals such as steel and aluminium are well suited. However, reusing these materials is also an energy-intensive process and, at a more detailed level, not all alloys and finishes can be reused. There are still too few plastics that are 100% recyclable.

But we diligently collect PET bottles?

Burri: It is only in the past few years that it has been possible to produce PET bottles from 100% recycled PET sourced from used PET bottles. This required the development of a new process, namely chemical recycling.

What obstacles still need to be overcome before our economy is truly circular?

Burri: The major challenges are posed by logistics and the different lifespans of products. The lifespan of a disposable product like a yoghurt pot is limited to the point in time that the yoghurt is eaten. A building whose structure may perhaps contain copper will stand for up to 50 or even 100 years. The places and times at which used materials are available again for new products therefore vary greatly.

“Mycelium, which is a fungal mesh, offers great potential as a natural material for circular products.”

Your institute has placed its focus on the circular economy, digitalisation and additive manufacturing. What specifically are you researching?

Burri: For example, we are developing products from mycelium, in other words from thread-like fungal filaments. This natural material offers great potential for things like packaging or the production of insulating mats. The big challenge is still to turn it into functional products, such as a bike helmet. This needs a special shape and must exhibit certain qualities, such as offering good protection and being comfortable to wear. The question is how can we achieve this in a manner that ensures our helmet offers at least the same level of protection and comfort as a conventional bike helmet? We are also researching cladding elements made from natural materials instead of plastics for vehicles as well as areas such as sustainable coffee capsules, insulation materials for buildings and a drilling robot for the drilling of geothermal probes. Last but not least, we are working on new mobility concepts and innovative vehicles, for example cargo bikes and bike trailers for logistics firms that they can use to efficiently deliver packages in cities.

You also head the Innovation Booster Applied Circular Sustainability on behalf of Innosuisse, the federal government’s Swiss Innovation Agency. What has been achieved here so far?

Burri: Since 2021, we have been promoting radical ideas from companies and start-ups and offering the relevant coaching together with other experts. These firms have a rough idea for a circular business model or product, but do not know how to turn it into reality, which materials would be suitable for their new product, what the logistics solution would have to look like or how they could earn money with it. This is where our expertise comes in. We organise “design thinking” workshops with these companies and, where necessary, bring in colleagues from other universities and specialist companies. We offer a launchpad for their ideas to take off from, so to speak.

“While these companies have a rough idea for a circular business model or product, they still have unanswered questions about how to turn it into reality.”

What inventive ideas have you encountered here?

Burri: Some examples include new construction methods for making a cellar out of wood, plans to produce a watch or clothes from new materials that should be recyclable and proposals for robust prams that have to be able to withstand being used as part of a sharing or pay-per-use model. To date, around 30 companies and start-ups have participated in the programme.

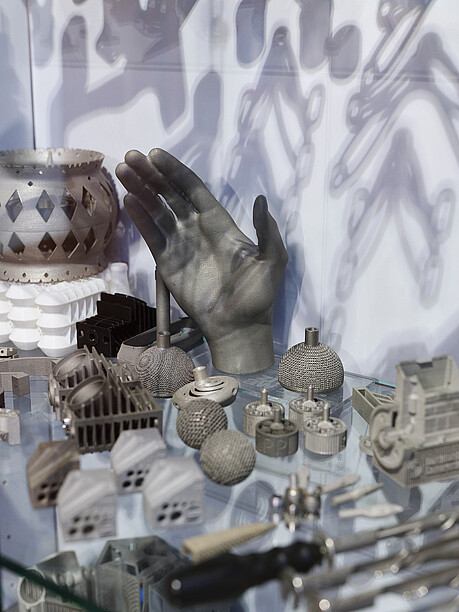

3D printing is in vogue. How recyclable are such products?

Burri: Essentially speaking, products from a 3D printer are not so recyclable. At the same time, however, additive processes are important for a sustainable economy. After all, 3D printing conserves resources due to less raw material being used, for example. In the aviation and automotive industries, it allows for lighter structures to be produced so that the end products used for propulsion in turn consume less energy. There are also lower logistics costs, as the components can be printed directly at the place of use.

So 3D printing is sustainable but not necessarily conducive to a circular economy?

Burri: We are working on this. In the near future, we want to explore how additive manufacturing could make a contribution to the circular economy at an open innovation workshop with 20 to 30 individuals from various companies. One topic here will be spare parts management. If I don’t have to build up stocks of spare parts and instead can simply create them using a 3D printer when I actually need them, this is a more sustainable set-up. The workshop will also look at the use of biomaterials in 3D printing that are ultimately compostable.

How much interest is there in circular solutions from the world of business as a whole?

Burri: There is an astonishing number of start-ups in Switzerland that are addressing this issue. This is pleasing. Among the established companies, however, there remains some reluctance.

Aligning existing companies with the circular economy is also a more complex undertaking.

Burri: That is correct. Here too, however, there are some encouraging examples. We held an open innovation workshop with the medical technology industry, with companies such as Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Ypsomed and Roche in attendance. The workshop looked at how to make their products recyclable. As thing stand, all consumables in a hospital – from surgical instruments to infusion bags – are disposed of after being used once in accordance with the applicable regulations and hygiene requirements.

“Here, a circular economy would in fact be no more expensive than the existing linear economy.”

What came out of the workshop?

Burri: The workshop gave rise to a consortium that is continually initiating new research projects in this field. It is very exciting to observe how actual competitors are working together to find solutions aimed at transforming this throwaway system into a circular one. Optimisation alone won't suffice. Products and business models need to be completely rethought.

When do you believe large parts of the economy will become circular?

Burri: By 2030, we will certainly see many companies participating in the circular economy, with completely different products made from new materials as well as different logistics and recycling processes. This will be driven by the corresponding laws. The EU is a pioneer in this area. Without laws, the pressure to bring about change quickly is not great enough. Here, a circular economy would in fact be no more expensive than the existing linear economy. On the contrary, it will in fact be ultimately cheaper if you don’t always have to buy new resources.

Institute of Product Development and Production Technologies

At the end of last year, the Council of the Zurich Universities of Applied Sciences and Arts approved the foundation of the Institute of Product Development and Production Technologies (IPP) at the ZHAW School of Engineering. It emerged from the former Centre for Product and Process Development (ZPP). The founding of the institute goes hand in hand with a realignment of the research activities conducted there, with the institute’s 34 researchers focusing on the circular economy, digitalisation and additive manufacturing. In order to hold their own on the market in the future, product ideas need to be designed in such a way that makes a closed material cycle possible. This is the only way to conserve resources, reduce CO2 emissions and allow for a sustainable, future-oriented economy. This requires new approaches in areas ranging from the selection of materials, product design and production itself right through to the use of the product and the associated business model. The institute, which has been the Leading House of the Innovation Booster Applied Circular Sustainability funded by Innosuisse since 2020, contributes its expertise to these interdisciplinary issues.

0 Comments

Be the First to Comment!