Hybrid diplomacy

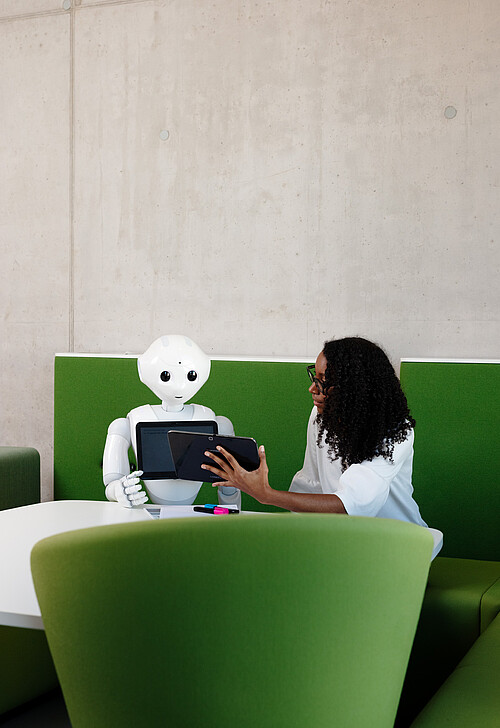

Digital transformation has changed the requirements placed on diplomats. People with an understanding of new technologies are increasingly being sought as bridge builders to Big Tech companies.

For a long time, virtual interactions were regarded as an inferior alternative to physical meetings. Then came the Covid-19 pandemic. The concomitant travel restrictions prompted changes in the world of diplomacy too. High-level meetings such as the G20 talks, Human Rights Council meetings in Geneva and the UN General Assembly in September 2020 were suddenly held as purely virtual or hybrid gatherings. In the world of diplomacy, where strict protocol had previously been part of everyday life, these traditions suddenly no longer played a prominent role. International meetings resembled completely normal business meetings conducted on a laptop. Rank and seating arrangements were no longer of any importance – the US representative was reduced to a small window on the screen just like the representative from Switzerland.

Impossibility to build up new trust virtually

In a study (“The Rise of Hybrid Diplomacy”) conducted by the two digital diplomacy researchers, Corneliu Bjola and Ilan Manor, the authors asked 130 diplomats how they perceived these changes. The result was, on the one hand, that it is certainly possible to “read” a virtual room, since the body language of one’s counterpart can be easily recognised today and the atmosphere in the room can be readily evaluated through the chat function. On the other hand, good meeting management takes on even greater importance in the digital space. Digital platforms are not, however, conducive to building trust with unknown discussion or negotiation partners – such a situation still calls for physical meetings. And last but not least, a certain “Zoom fatigue” was also mentioned as an obstacle to virtual or hybrid diplomacy. When controversial issues arise, reaching an agreement takes considerably more time in an online setting than offline. This is frequently felt to be particularly tiring.

Certain government representatives are sceptical about data privacy and data security when using the customary conference tools. Zoom and Microsoft Teams are only permitted for discussions on public topics and not for confidential contents or internal meetings, as was recently seen at a symposium for EURAM, the largest European conference for the management sciences, hosted by the School of Management and Law.

Technological expertise versus mobility

Not only the tools have changed however. The professional profile of a diplomat is also changing with digitisation. Today, foreign ministries are hiring increasing numbers of people who have previously worked in the private sector and the tech field. A good understanding of new technologies and their ecosystem is now a prerequisite for survival in the new world of international relations. In a number of countries, this also means moving away from the traditional system of relocation logic, where diplomatic personnel are assigned a new position or posted to a new country every three to four years. Today, a number of foreign ministries attach more importance to a candidate’s willingness to acquire a certain technological expertise and develop it over a prolonged period of time than to their readiness to accept mobility.

Are older employees being left out in the cold?

Even if older employees have not grown up with many of these new technological possibilities, there is no evidence that different abilities in mastering them boil down to a question of age. This is because it is not the specific technological know-how that someone has to master but rather the concepts and mode of operation of these new tools. Against this background, a number of countries have started making their top diplomats more aware of social media before they are posted to a new country. The representatives are to be capable of identifying which instruments and channels constitute suitable working tools in specific cultural contexts.

Digital sovereignty constitutes a key challenge especially for small countries, since they are dependent on foreign Big Tech companies both for the public cloud, i.e. how and where data is stored, and for numerous other IT applications. Diplomats are thus frequently required to establish contact with these major companies today and anticipate and analyse developments in the tech sector. Denmark was the first country to recognise this in 2017, sending a Tech Ambassador to California’s Silicon Valley and, a year later, to Beijing.

Estonia’s “Data Embassy”

Estonia, for example, wished to become independent in matters of data storage and has built up its own data centre in Luxembourg under Estonian sovereignty. The small state now has a “data embassy” with backups of the country’s most important systems. According to Nele Leosk, Ambassador-at-Large for Digital Affairs at the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the work of diplomats also includes supporting the institutions of their country that deal with digital governance – such as in negotiations with Big Tech regarding IT infrastructure. Numerous examples, however, show just how challenging bridge-building between governments and Big Tech is. The doors in Silicon Valley very often remain closed to small and medium-sized countries. This autumn, the EU is intending to send a Tech Ambassador to Silicon Valley for the first time to help facilitate cooperation between regulators and the big technology companies.

*Dominique Ursprung is Deputy Head of the Center for Global Competitiveness at ZHAW

0 Comments

Be the First to Comment!