Reaching for the stars

As part of the Academic Space Initiative Switzerland (ARIS), students from several Swiss universities are independently developing systems for scientific space flight. A visit to the hangar.

It is 10 a.m. and there is a buzz of activity on the grounds of the military airfield in Dübendorf. Where fighter jets once roared into the sky, several student working groups are now tinkering with their projects. The site is evolving into an innovation hub that will one day be the largest in Europe. And right in the middle of all of this is the Academic Space Initiative Switzerland, or ARIS for short.

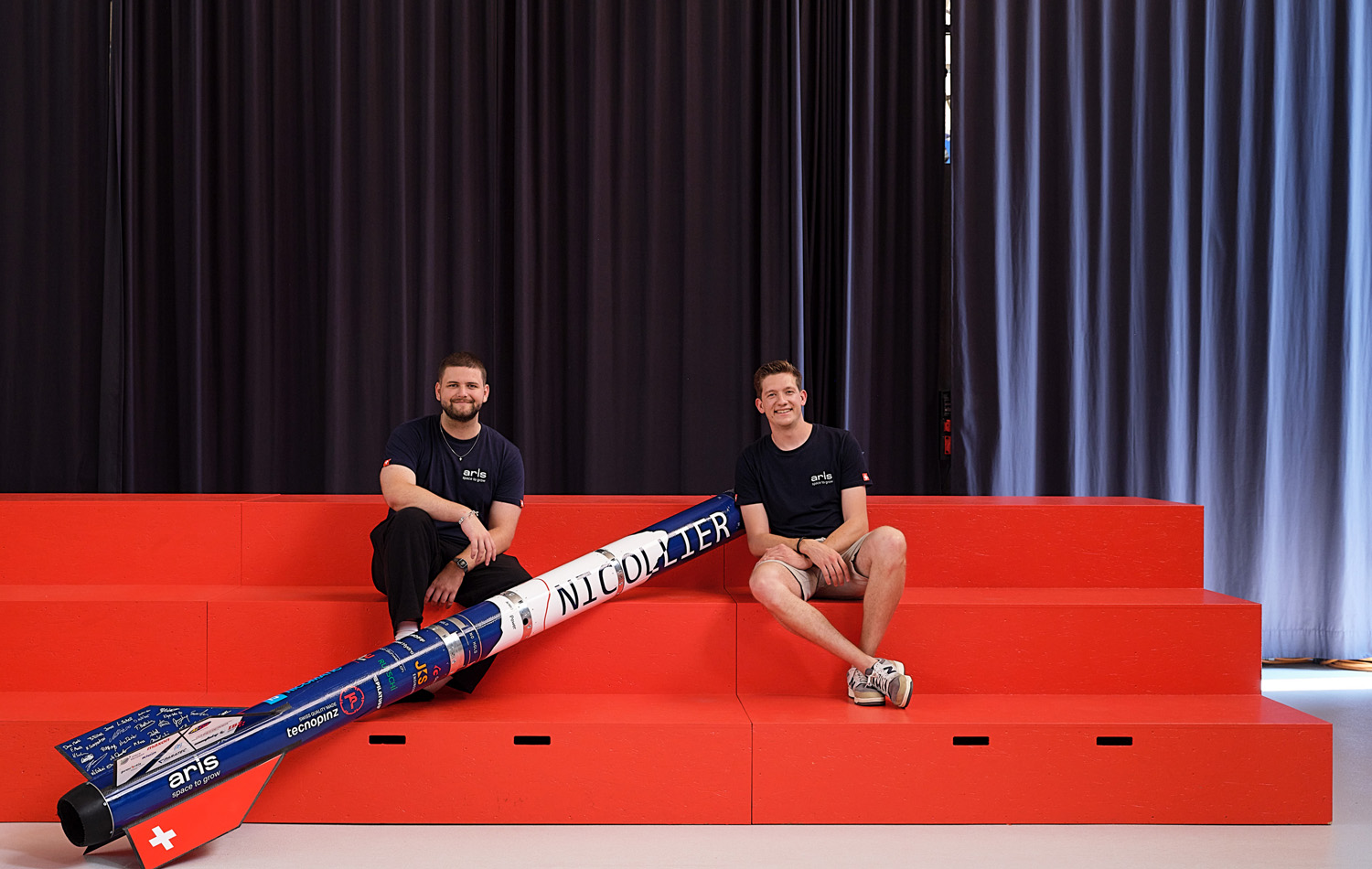

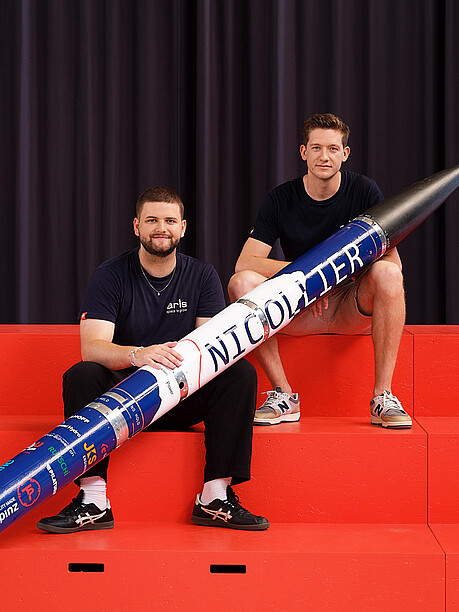

In the ARIS workspace, what can be referred to as organised chaos prevails: cabinets, shelves with all manners of tools, a large table with laptops, a model of a rocket engine, a pallet of energy drinks, a couch and three rockets positioned nonchalantly in the background. One of them is the “Nicollier” sounding rocket. Sounding rockets are unmanned rockets that take physical measurements in the atmosphere during flight. Thanks to an integrated recovery system, they can be reused. In 2024, ARIS successfully launched NICOLLIER to an altitude of 1,000 metres several times and landed it safely just a few metres from the target site. The altitude record stands at over 10 kilometres.

Founded in 2017 by ETH students, around 200 students from five different Swiss universities are now involved in ARIS: the ETH, the ZHAW, the University of Zurich, the Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences and the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts. They independently implement ambitious space-related projects that range from sounding rockets and robotic systems to satellites. These projects are made possible by sponsors who contribute financially or provide components. The initiative can now count on support from approximately 80 partner companies.

Nine kilometres in the sky

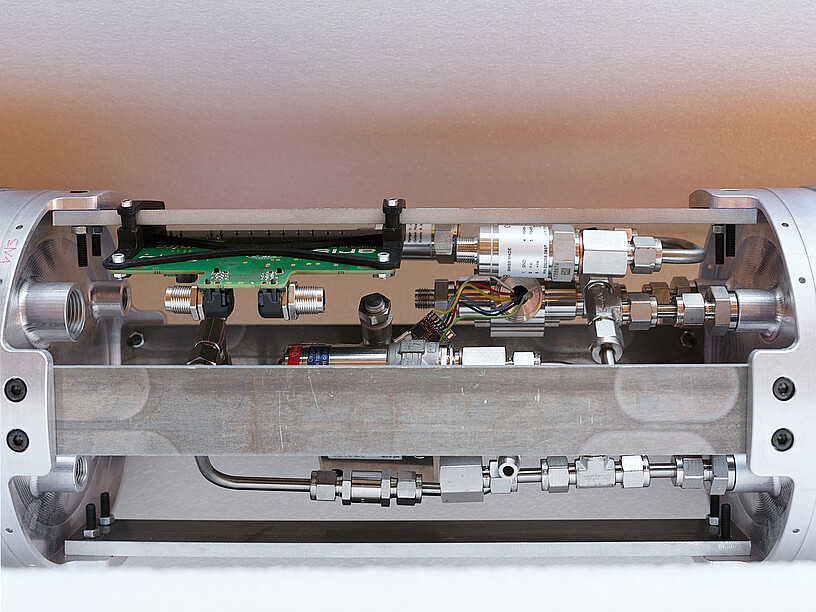

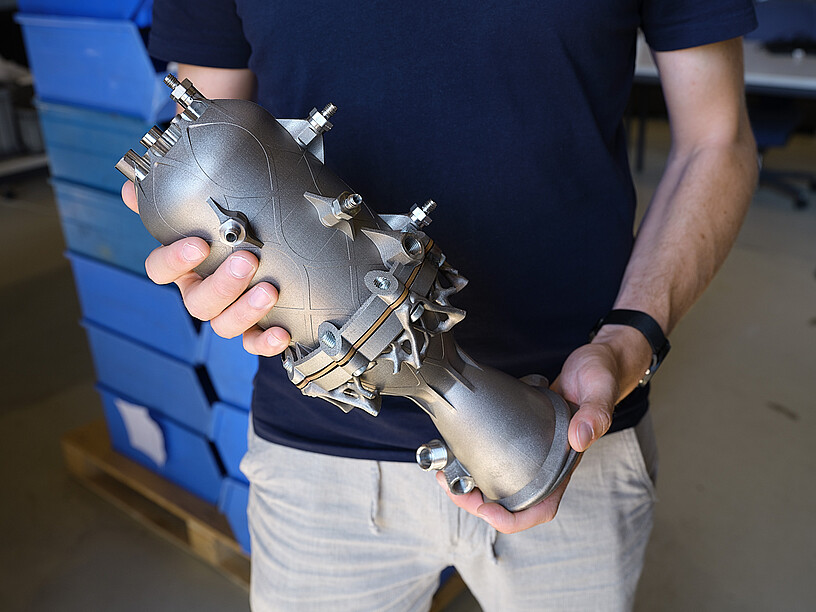

So, is Switzerland a spacefaring nation? “Not in the traditional sense,” explains Jakob Schreiber. The 25-year-old is currently studying for a Master’s degree in Engineering in Aviation and is also a research associate at the Centre for Aviation at the ZHAW School of Engineering. “However, Swiss companies do play a key role in the supply chain by developing high-precision technology. For example, they develop applications for navigation, communication and Earth observation.” In last year's “Nicollier” project, Schreiber and six other students were responsible for electronics and software development. In the current “Hermes” rocket project, he is one of the system engineers as well as operating as the project’s technical lead and flight director. In other words, he is the person who gives the green light to launch the rockets. With “Hermes”, ARIS is aiming to be the first student team in Europe to develop a sounding rocket powered by an ethanol-oxygen propulsion system. The goal is to propel the rocket around nine kilometres into the sky at a speed of approximately 1,400 km/h.

Exploring Saturn and the poles

Alongside Schreiber, six other ZHAW students are currently involved in ARIS. One of them is Victor Elliesen, who is studying international management at the School of Management and Law. The 22-year-old has several roles at ARIS: he is Vice President, Head of Industrial Relations and Project Manager. In his “Nautilus” project, the team is developing an unmanned underwater vehicle that collects scientific data. Elliesen explains: “Existing systems can only remain underwater for a few weeks at a time. Our goal is for “Nautilus” to operate at depths of 300 metres for up to three months.” The team is being supported by Eawag, the ETH Domain’s Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology. The long-term objective is to use “Nautilus” to explore Saturn's icy moons. The propellerless glider is, however, also suitable for use on Earth, for example for polar research. Simulated polar tests in Norway are planned for 2026.

Learning by doing

Listening to the students talk, the question naturally arises as to where they got their expertise for such highly complex work from – after all, this is literally rocket science. “Much of it is learning by doing,” says Schreiber. “My aviation studies gave me a solid understanding of technology, physics and methodological approaches, and taught me how to acquire knowledge independently. However, not all of the participants have a technical background, neither has Elliesen. “As in any company, a variety of skills are also needed at ARIS,” he says. Interdisciplinary sub-teams that provide the necessary expertise are defined for each project. ETH students typically come from suitable technical degree programmes, while those from the ZHAW often have work experience, which is very welcome. Elliesen explains: “You also need people who understand the big picture. I would not be able to programme a control system, but I can talk to potential sponsors. Today, I even discuss alloys and production processes with them based on knowledge that I have acquired myself.

Hands-on experience

The work at ARIS is voluntary. For Elliesen and Schreiber, however, the experience is priceless: “What motivates me the most is developing highly complex systems independently,” says Schreiber. “The level of responsibility we take on is enormous – we work with 300-bar pressure and liquid oxygen, for example. Here, you learn as much within one year as you might at best learn during five years at a company.” Elliesen adds: “If you are interested and want to take on responsibility, there is no better place to be. Some teams have 50 members, and the Board oversees 200 people. This requires skills that you won’t learn in any classroom.” For a student organisation, the size of the budget is also nothing to be sneezed at: in 2024, ARIS received more than CHF 850,000 in the form of financial and in-kind contributions. Networking with like-minded people is another major benefit. “The motivation within the team is enormous. And today, every major aerospace company employs former ARIS members. Rabea Rogge, who became the first German woman in space in 2024, is also an ARIS alumna,” reports Elliesen. “Many alumni stay in contact with the association and provide us with advice and hands-on support.”

At the Federal Palace and the World Expo

The fact that ARIS is perceived as a serious player in the space sector is evident from two recent high-profile invitations: Elliesen and three of his colleagues contributed their expertise to the National Council during the consultation procedure for the planned Swiss Space Law, while Swissnex invited ARIS to represent Switzerland’s space industry at the World Expo in Osaka. There, they also visited the Swiss Consulate, where they exchanged ideas and experiences with Osaka Metropolitan University. “Realising that we can truly make an impact was hugely motivating,” says Elliesen. Schreiber also shares that he really enjoys the feeling of getting something off the ground together with a team: “The fascination is like a pull that is almost impossible to escape. I admit that I have discussed technical details at 2 a.m. in a bar.”

Over the longer term, both see themselves in their own start-ups. “The way in which we work at ARIS is my ideal vision: innovative projects, fast processes and a motivated team,” Schreiber enthuses. The association has also set itself the goal of launching several spin-offs over the next few years. Elliesen: “The time is ripe, Europe needs to become more autonomous when it comes to space travel. The expertise is certainly there – and motivated students can reach out to us at any time.”

0 Comments

Be the First to Comment!