When our bodies age

Why do our bodies age and how can we slow down the processes involved? These are questions occupying both researchers and the anti-ageing industry. The aim is to live out the last years of our life with as few complaints as possible.

Car tyres suffer abrasion over time, the gears on a bicycle are subject to wear and tear and wooden facades become weathered due to the rain and sun. Just like any other material, the human body is also permanently exposed to chemical and physical stress. This stress adds up as we get older – and the body ages. "We are made of matter and this is subject to the ravages of time,” says Michael Raghunath, Head of the Centre for Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering. How this ageing process can be stopped constitutes a huge field of research. “Life expectancy has increased considerably thanks to modern medicine. It’s now a matter of increasing our health span too so as to ensure that we remain as healthy and fit as possible throughout the last few years of our life.”

In the beginning there are the cells

Ageing processes in the body take place at the level of the cells. Just as oxygen causes metals to rust, cells are also damaged by oxidative processes. And the UV radiation that makes plastics brittle also attacks our skin cells. Contrary to dead matter, however, our bodies are capable of replacing damaged cells. Cells in our skin, intestines and lungs renew themselves regularly by division. This process cannot be repeated at will, however, since the number of cell divisions is limited. Slight mishaps can also occur each time a cell divides, with part of the genetic information being lost or mutating, for example. These errors add up over time. One consequence of this is that cells can multiply uncontrollably, causing cancer to develop.

“If the body is not supplied with essential amino acids, the liver helps itself to muscle protein.”

The cells in other organs hardly divide at all. If one of these cells suffers damage, the so-called stem cells go into action. Stem cells can divide several times over and are able to develop into different types of cell. They thus jump in and fill the gap. They also get tired as they age, however, and their number declines. Different approaches to stopping cell ageing are being researched – selectively switching off damaged and aged cells, stimulating cell division again or reducing chemical stress. One example is antioxidants, which bind free radicals and thus prevent them from attacking cells.

Loss of mobility and strength

Something that has less to do with cell renewal is the loss of mobility in our bodies over time. This is due more to progressive cross-linking. Different types of sugar circulate in the blood in order to supply our organs with energy. They also make their way into the connective tissue, where they cause the collagen in tendons, ligaments, skin, capsules and blood vessels to stick together. If our bodies become stiffer, we move less and our muscles degenerate. The loss of muscle mass is a typical sign of ageing, but it is not associated solely with how much we exercise. The food we eat is also important, Raghunath explains: "If the body is not supplied with essential amino acids, the liver helps itself to muscle protein to provide them.” And muscle cells are ultimately subject to the ageing process too.

“We used a 3D printer to print satellite cells from muscles between two posts. Within about two weeks they had developed into whole muscle fibres.”

Muscles play a central role in ensuring an independent life into old age - they are important for a healthy basal metabolic rate and weight control, as well as for maintaining balance and preventing falls. Muscle activity is also important for bone stability and density. Studying the ageing process of muscles and finding substances to slow their degradation is therefore one of the many areas of research being pursued by the anti-ageing industry.

Studying muscles in a model

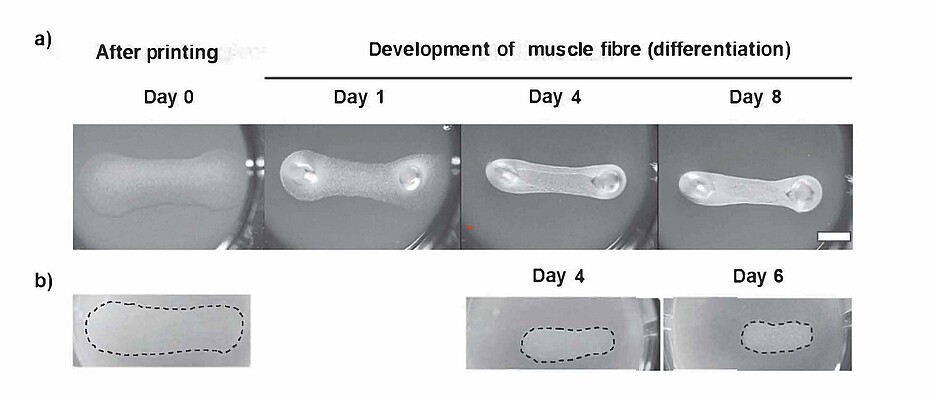

Working together with a pharmaceutical company, ZHAW’s Section of 3D Tissues and Biofabrication has developed a model of a skeletal muscle. “A muscle has so-called satellite cells”, explains researcher Markus Rimann. “These are a kind of stem cell that develops into muscle cells when needed and then fuses to form the long muscle fibres. The muscle can then regenerate if it gets injured, for example.” Rimann’s group has used a 3D printer to print satellite cells of this type between two posts. Within about two weeks, the satellite cells had developed into whole muscle fibres and joined onto the posts in the same way as the muscles in the body attach to the bones. “If we stimulate this muscle with electric current, it contracts and bends the posts,” Rimann explains. The stronger the current, the greater the degree of bending flection and hence the greater the strength.

Human satellite cells from a 3D printer

If a substance is added to the muscle model, it is possible to measure whether this increases or reduces the degree of bending. "Various substances, such as caffeine, are known to have a positive effect on muscle strength,” says Rimann. “We have tested the model with these substances and shown that it reacts like a natural muscle." In future, muscle models such as these could be made from cells of people of different ages or with muscular diseases as a means of studying muscle function and the different effects of substances.

Exercising and generous seasoning

Currently, there is no remedy in sight for stopping muscle loss in old age. This does not, however, mean that we are powerless, as Michael Raghunath explains: "Exercise and selective muscle training are extremely important for staying fit into old age." A balanced diet is decisive too. The physician also has some advice to offer in this respect. "Because people’s sense of taste diminishes with age, food seems less tasty and people lose their appetite. My recipe for countering this is to simply season dishes a little more so that eating is still enjoyable. – And food tastes best in company!"

0 Comments

Be the First to Comment!