“Nature and the city are intertwined”

How can urban and natural regeneration succeed? And is it possible to reconcile nature conservation interests with the way we spend our leisure time? Two ZHAW experts from the areas of urban planning and environmental engineering address these questions in the following interview.

Regeneration is synonymous with renewal and revitalisation and is thus considered to be a key component of solutions where sustainability concepts based on preservation and the conservation of resources are not enough. Such scenarios include ecosystems and urban environments that have been pushed beyond their limits, as well as depleted soils, dwindling resources, scarce energy supplies, accelerated climate change and a performance society in which we are exposed to ever more stress. The ZHAW is conducting research in the search for answers to how we are to overcome these problems.

Crises, wars and conflicts – the world seems to be in a state of constant stress. Faced with the many challenges of our time, people are longing for regeneration. At a completely personal level, how do you recuperate at the end of a stressful working day, Mr Krebs?

Rolf Krebs: I like to head out on walks, ride my bike or hit the slopes, ideally in natural surroundings. Luckily enough, I don't live far away from the forest.

What is your recipe for success, Mr Kurath?

Stefan Kurath: I try to avoid stress as much as possible. I like going to a café to drink a coffee and read the newspaper. However, I also enjoy doing sports, including mountain biking, whitewater kayaking and skiing.

Looking at the research being conducted into saving the planet, it seems that sustainability has had its day. Regeneration is now the word on everyone's lips.

Kurath: In my view, rapidly changing terminology and trends are more of an expression of the severity of the crisis we are facing. If a problem can’t be solved, you approach it from a slightly different perspective and come up with a new concept.

Krebs: I have to disagree here. The concept of sustainability remains key. This is true not only for our institute but for the ZHAW as a whole. However, I do consider certain ideas in connection with regeneration to be very important. I would like to explain this by drawing on an example from my own specialist area of soil. Many soils have already been damaged by intensive cultivation practices of the past and have an inadequate organic matter content. Regenerative agriculture is now being used to ensure the fertility of our soils in the long term by restoring this organic matter content. The idea of using natural resources in a sustainable manner is no longer sufficient in every instance.

Kurath: There is no doubt that sustainability and regeneration are important. The problem I see with trends is that everyone turns their focus to the same issue and ignores everything else. Sustainability has always been a fundamental issue in architecture. There is a focus on sufficiency, consistency and efficiency. After all, as architects we want to do something good in this world.

Is this really the case? Many people assume that your profession is chiefly concerned with self-fulfilment, while environmental engineers endeavour to reconcile the tension that exists between people and their natural surroundings.

Kurath: That really is an unfair preconception that has been exaggerated by the media. Even star architects usually take a variety of sustainability aspects into consideration. Let’s take the example of Herzog & de Meuron and its building on the Chäserrugg for Toggenburg Bergbahnen AG. The building is the result of an in-depth examination of both nature and landscape conservation. In order not to cause too much stress for the chamois and other animals that live in the area, the construction processes completed on site were kept to a minimum and wood was used as a building material due to the fact that it could be transported up the mountain using the lift instead of by helicopter. The Swiss Landscape Conservation Foundation thus named the Chäserrugg/Toggenburg tourism infrastructure as "Landscape of the Year” in 2021.

Is the circular economy the solution to regenerating our planet and bringing about climate neutrality?

Krebs: I would say that it is an important concept for helping us move in the desired direction. However, as it is so comprehensive, it isn't something that can be implemented from one day to the next.

Where should we start?

Krebs: With the way in which we plan and design our products, buildings and processes. From the very outset, we need to consider the longevity and recycling of the materials and substances we use. This is something we teach in the new interdisciplinary Master's degree programme in Circular Economy Management, which was successfully launched in the autumn semester with more than 30 students on board.

Kurath: Until 150 years ago, it would never have passed through somebody’s mind to rip down existing houses, dump the used materials on a rubbish tip and bring in new ones from China. In the past, structures were preserved and the materials put to further use. With industrialisation and technologisation and the prosperity these processes have brought us, development has taken on a different dynamic – one of complete idling, as we now know. This is something we have to change.

Dismantling and recycling are issues that are also increasingly being talked about in connection with buildings.

Kurath: In my view, building today in a manner that means we can dismantle everything 30 years from now is a misinterpretation of the circular economy. The construction of a building involves the consumption of a great deal of grey energy, for example in connection with the concrete components. We need to think much more long term here and be open to different uses. The spatial structures found in Zurich’s city centre have existed for centuries. The ground floors of buildings where people used to work are now home to stores selling trainers, while the upper floors where people once lived are now used as storage spaces for the cardboard shoeboxes, for example. So why not convert currently redundant office buildings into flats instead of tearing them down? Spatial structures can accommodate many more uses than we might think.

At the end of 2022, approximately 85 percent of Switzerland’s permanent resident population lived in urban areas. What do regenerative cities have to look like in order to be able to offer a good quality of life and counteract climate change?

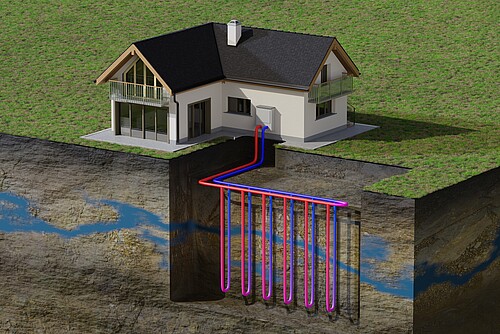

Krebs: Close-to-nature construction practices that include green outdoor elements such as roofs and façades, as well as designing public spaces to integrate trees, for example, play an important role in making cities more people- and climate-friendly. In summer, the way we experience heat is much more extreme in unshaded areas than when walking through areas lined by trees. Cities are also increasingly becoming part of our food systems, for example through urban farming concepts.

And yet squares are still being built that are covered with concrete or stone, such as Sechseläutenplatz in Zurich.

Kurath: What is being built today was planned 10 to 15 years ago. Back then, environmental considerations were not as prominent in people’s minds as they are today. Sechseläutenplatz would look very different if it were to be planned now. Planning simply moves at a much slower pace than social change. There is also the fact that cities have little to do with how architects or urban planners would conceive or design them. They are the result of negotiation processes played out at a societal level. Covering squares with stone or concrete and this sense of inhospitality and confusion that we observe out there is chiefly down to the strong assertiveness of individual interests. Unfortunately, planning still has too little impact.

What individual interests are you referring to here?

Kurath: In most cases, focus is placed on maintenance and ease of cleaning. The climate problem has thus far been of secondary importance in the area of urban planning. This is now changing. Today, its about development inwards, densification and ensuring an appropriate mix of uses, meaning that people only have to travel short distances thanks to the healthy ratio between jobs and the resident population. Local materials are being used to enhance quality, re-use issues are being addressed, and we are seeing greening and green space networking being promoted. We are also observing adaptations brought on by climate change considerations, such as sponge cities that absorb water during heavy rainfall and later cool the urban spaces through evaporation. The implementation of such concepts is becoming increasingly urgent.

How can individual interests be overcome?

Krebs: What we need is a social consensus with respect to environmental priorities. An example of this can be seen in the canton of Basel-Stadt. The people of Basel have decided that green roofs should be promoted and have enshrined this in the canton’s Building Act. As a result, Basel-Stadt is one of the urban areas with the most green roofs anywhere in the world.

“Planning simply moves at a much slower pace than social change.”

Kurath: Change usually leads to resistance in people at first. I am currently writing about this and about how society’s willingness to change increases during times of crisis. Throughout the history of urban planning, it has been crises such as fire, plague, cholera, revolution and war that have given rise to the greatest changes. Today too, against the backdrop of the various crises we are facing, you get the sense that much more is now possible in terms of planning than was the case previously: it is no longer necessary to talk with clients about why things like shading, drainage and liveability are essential aspects in the context of the climate crisis.

Krebs: Environmental issues arise directly as part of construction projects and conflicts of interest become apparent. I can give you another example here relating to soil: as soon as a building is finished, the gardener gets to work on the surrounding area. The subsoil is applied to the raw soil and routinely compacted with machines. This is done as otherwise the topsoil won’t remain level over the long term and customers will enforce guarantee agreements to rectify this. As a soil scientist, however, I have to prevent the subsoil from becoming compacted, as this can be detrimental to soil fertility over a long period of time. This means that we require communication and a joint effort to find viable solutions.

Which brings us back to the topic of individual interests. Apart from gardens, how can we bring natural landscapes to urban areas?

Kurath: Nature doesn't have to reclaim our cities, as is sometimes demanded. If we look closely, there has always been and still is an interplay between natural and non-natural elements in urban settlement areas. This is true despite the fact that natural elements have been heavily displaced. However, it would not be difficult to massively enhance this urban fauna and flora by taking appropriate measures.

“What we need is a social consensus with respect to environmental priorities.”

Krebs: In addition to long-term planning, a great deal can also be achieved in the short term and with little effort and expense. For example, roadside greening measures that use seed mixtures incorporating numerous native plants can contribute to greater biodiversity. Our research has revealed which of these seed mixtures are less demanding to maintain. In the case of green roofs too, there are relatively simple design elements available that help to maximise biodiversity or water storage.

Your institute also conducts projects that look at wild orchids on green roofs or amphibians and beetles in urban areas.

Krebs: That is correct. The city is already home to a rich range of biodiversity, with more than a thousand foxes now living in Zurich, for instance. However, biodiversity can also be promoted and further enhanced in a targeted fashion. Intensive research in this area is being conducted in our Urban Ecosystems Research Unit.

“The city is already home to biodiversity, with more than a thousand foxes now living in Zurich, for instance.”

Kurath: It has even been found that levels of biodiversity are greater in the city than they are in areas where monoculture agriculture is practised.

How can our natural and city landscapes by reconciled?

Krebs: I am convinced that the two do not have to be opposites. In fact, they intertwine with each other. This is also reflected in our degree programme for budding environmental engineers. Urban ecosystems are becoming increasingly important. The focus here is on adapting to climate change, biodiversity and sustainable food systems in cities. This trend has intensified over recent years. The challenges have to be tackled together with specialists from the realms of architecture and planning.

Why do we need nature conservation and wildlife sanctuary zones outside our cities? Are these actually more than simply fig leaves?

Krebs: The pressure on semi-natural zones is steadily increasing due to the utilisation demands humans place on them. Such conflicts with respect to use are key to our research. For example, visitor management in mountain landscapes or local recreation areas, such as the Uetliberg in Zurich. Here, concepts are being developed with the aim of reconciling the interests of mountain bikers and pedestrians from the city with the needs of the semi-natural ecosystem. We also clarify for cantons where wildlife sanctuary zones are needed in order to ensure the survival of wild animals.

Is there also room for the wolf?

Krebs: We have investigated where and how wolf populations are developing. It is possible to assign the animals to a pack on the basis of their calls. This helps us to understand how they move and behave. We are keen to ensure that such issues are discussed at an expert level and are not solely dealt with by politicians.

“It has even been found that levels of biodiversity are greater in the city than they are in areas where monoculture agriculture is practised.”

Kurath: My father-in-law was a gamekeeper. Bears and wolves had both become a major issue for him again in recent years. Personally, I find it interesting how people view wolves in mountain areas. Farmers, for example, keep dogs, which at the end of the day are nothing more than domesticated wolves. And these dogs perform valuable work by protecting the farm and the animals it is home to. On the other side of the coin, their primal predecessors, which cause damage and kill sheep, are fought against. However, the domesticated wolves are also fed with meat from the farm. It is a somewhat curious situation. The issue of how to deal with wolves remains a little tense.

Krebs: The shooting of wolves is just the tip of the iceberg as regards this utilisation conflict. After all, wolves as predators are actually a natural part of our ecosystem. They decimate sick and weak animals and keep semi-natural areas in balance.

Finally, let’s take a look ahead: what will the urban landscapes of the future look like?

Kurath: If planning efficiency were greater, things would look very different out there. As architects, we therefore have to get better at incorporating issues like climate adaptation, the importance of local building materials and an awareness of quality into these social negotiation processes. This would result in our cities and urban landscapes, as well as semi-natural cultural landscapes, being far more diverse and of a higher quality. What is more, they would also be more beautiful and liveable.

What will the natural landscapes of the future look like?

Krebs: I would like to see semi-natural landscapes that offer more space for biodiversity. They should provide people with space for rest and recreation and allow for responsible use by incorporating renewable energy and circular economy approaches. I am convinced that we first need a social consensus on what we really want and need. Once this is in place, it will be possible to achieve a great deal.

Regeneration

We talk about regeneration when an individual recovers energy that has been consumed or lost, for example when doing sports or due to illness. In the fields of biology and medicine, the term is also used to refer to the natural restoration of injured or dead tissue. Ecosystems, in turn, regenerate when they reverse a negative impact or an imbalance. Regenerative agriculture promotes soil health and biodiversity. In technical terms, regeneration also refers to the restoration of certain physical or chemical properties of something or, for instance, the recovery of usable chemical substances from used and contaminated materials. In comparison to sustainability, which aims to ensure the preservation and careful handling of things as they currently are, regeneration is about reactivation and actively restoring an ecosystem’s balance.

Glossary

Regenerative city:

The regenerative city is a concept of a community that integrates itself into its surrounding ecosystems and does not destroy them. It develops in a manner in which its ecological footprint is minimised. Key components of this concept include urban farming and ensuring short travel distances by having work or shopping facilities in the local area as well as embracing circular economy and zero waste approaches, among others.

Sufficiency:

The endeavour to lower the use of resources such as energy and materials by reducing consumption and utilising fewer services. It involves scrutinising what is actually needed.

Consistency:

The search for alternative technologies and materials that are better for nature and the environment than previous ones and the endeavour to close cycles from the production and usage stages right through to recycling and reuse.

Efficiency:

The more efficient utilisation of raw materials and resources, often through the use of technical innovations.

0 Comments

Be the First to Comment!